Despite most Bhutanese consuming almost double the amount of WHO recommended daily salt intake, the number of households consuming iodised salt has dropped to 95 per cent over the last decade. The rate was almost 100 per cent in 2015. This is according to the recently published National Health Survey. Health officials said this could threaten Bhutan’s reputation of having eliminated Iodine Deficiency Disorder as a public health concern in 2003. This disorder is the major cause of preventable mental retardation and the common cause of goitre.

The National Health Survey collected a total of over 1500 urine samples from pregnant and lactating women along with children aged six to 12 to check the presence of iodine in their urine.

The survey found that urinary iodine excretions have decreased significantly since 2010.

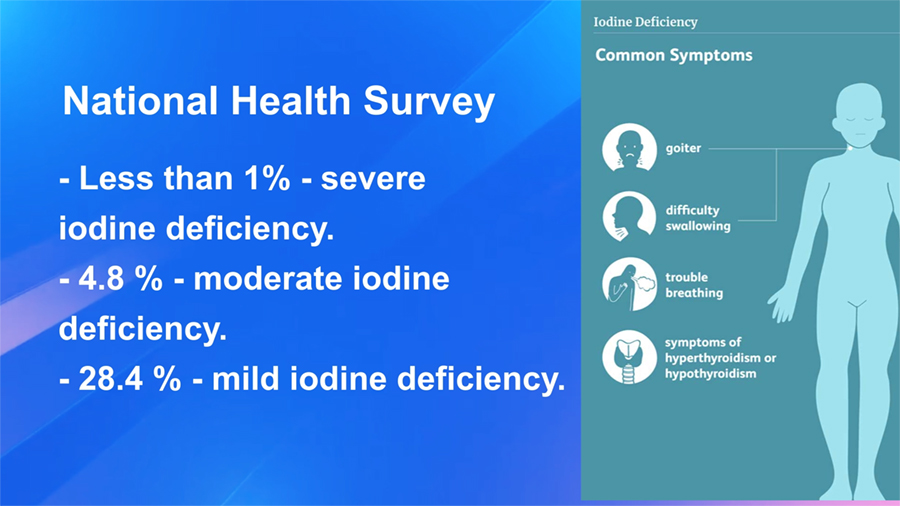

It also revealed that less than 1 per cent of the surveyed population had severe iodine deficiency, about five per cent had moderate deficiency, and almost 30 per cent were found with mild iodine deficiency.

The survey also collected salt samples from almost 12,000 households to check iodine concentration.

Mongal Singh Gurung, Medical Statistician of Policy and Planning Department said “So surprisingly, only 95 percent of the households have salt that contains iodine. So this is a very sad reality for the country. So, our achievement in eliminating iodine deficiency disorder might come back if this is the trend and if we do not do a timely intervention.”

However, the current figure is not below the threshold of iodised salt coverage. Despite this, the health ministry said people should consume iodised salt.

Hari Prasad Pokhrel, a nutritionist at the Department of Public Health said “Now, we would like to request and urge our population, all the consumers, to try and read the labels and only consume iodised salts. So, one popular salt brand that the consumption is picking up in the country is pink salt. So, through our analysis, we found out that this particular salt does not have adequate iodine.”

Mongal Singh Gurung, medical statistician said “So, in order to prevent the salt from melting, people in the village keep near the oven. So, in the process, actually all the iodine will evaporate. So, there are techniques. So, even in terms of NCD reduction, you will have to add the salt at the end so that everything will not go out. That is good for even reducing the salt as well as preserving.”

The officials added that they are planning to revitalise the Iodine Deficiency Disorder Control Programme, and advocate more on the importance of consuming iodised salt.

Meanwhile, people are mostly negligent of checking labels when buying salt and following iodine preservation methods.

Dorji, a resident said “When it comes to salt, I do not check the labels as it comes in a package. I just go there, ask for the price, and buy it. Then, when I reach home, I just pour it in a container and keep it beside the gas stove. ”

“When I buy salt, I do not check anything and immediately buy it. Even when I put salt while cooking if the first portion is not enough, I put it again,” said Phuntsho Wangdi, another resident.

Currently, there are no regulations and agencies to monitor whether salt brands sold in the market have adequate iodine or not.

The Royal Centre for Disease Control only tests salt samples that the health ministry or other agencies send to them.

Vishal Chhetri, a medical laboratory technologist said “For the salt iodine, the Royal Centre for Disease Control, is doing the titration method whereby we are actually quantifying the amount of iodine in the salts that are available in the market.”

According to UNICEF iodine deficiency is especially damaging during pregnancy and in early childhood. In the most severe forms, the deficiency can lead to abnormal mental and physical development, stillbirth and miscarriage. Moreover, mild deficiency can cause a significant loss of learning ability.

Singye Dema

Edited by Kipchu