People living near the Pasakha Industrial Estate in Phuentshogling are already bearing the brunt of air pollution caused by factories. With little done to compensate affected communities, residents continue to wait for relevant authorities to take action. However, the lack of sufficient data and research on the impacts of air pollution has made it difficult to address the issue.

People living near the Pasakha Industrial Estate in Phuentshogling are already bearing the brunt of air pollution caused by factories. With little done to compensate affected communities, residents continue to wait for relevant authorities to take action. However, the lack of sufficient data and research on the impacts of air pollution has made it difficult to address the issue.

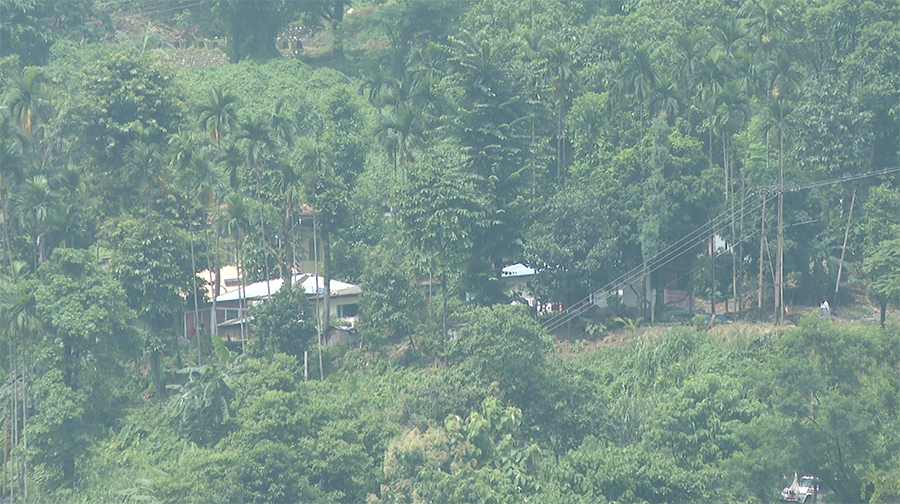

Nearly 40 factories operate in the Pasakha Industrial Estate. While they have created jobs and spurred development, residents of Samphelling Gewog live with pollution every day.

Nearly 40 factories operate in the Pasakha Industrial Estate. While they have created jobs and spurred development, residents of Samphelling Gewog live with pollution every day.

69-year-old Jagay Rai has lived in Sengyegang long before the factories arrived.

Jagay Rai said, “There was nothing here back then. It was just our village and our farms. We used to grow areca nut, maize, and other vegetables. Now, we don’t even have clean drinking water. Everything is being destroyed by chemicals. In those days, we didn’t even know what chemicals were, as we were illiterate.”

Jagay Rai said, “There was nothing here back then. It was just our village and our farms. We used to grow areca nut, maize, and other vegetables. Now, we don’t even have clean drinking water. Everything is being destroyed by chemicals. In those days, we didn’t even know what chemicals were, as we were illiterate.”

He says thick smoke and dust from factory chimneys settle on clothes and roofs. Noise from heavy vehicles has become part of daily life.

Villagers can no longer grow vegetables or fruits. Their only reliable source of income now is areca nuts.

Villagers can no longer grow vegetables or fruits. Their only reliable source of income now is areca nuts.

“I worry about what my grandchildren will grow and eat in the future. They are still studying now, but this problem won’t just affect my grandchildren; it will impact the generations to come in our village,” added Jagay Rai.

Despite these impacts, residents claim they have received neither compensation nor any support from the factories.

Samphelling Mangmi Khemraj Limbu said, “People are losing interest in agriculture. In the villages, even the CGI sheets on our roofs are getting damaged. They start rusting within just two years. The water, too, gets contaminated because of dust particles. I believe air pollution is affecting our health. We have raised these concerns several times, even through the gewog office, but so far, no relevant office or agency has taken any action.”

Phuentshogling Thrompon Uttar Kumar Rai said, “If someone is making a profit while others are suffering, that’s not right. Everyone should benefit. In that sense, the affected people deserve some form of compensation, whether in cash or kind. It doesn’t necessarily have to be a direct cash payment; support through corporate social responsibility initiatives would also make a difference. Otherwise, at the very least, those living in the area should be given employment opportunities.”

BBS reached out to the Association of Bhutanese Industries to confirm about Corporate Social Responsibility and emission control within the factories. However, we have yet to receive a response.

Without research and data, the problem remains invisible.

Health officials admit that no research has ever been carried out to determine the impact of pollution on people’s health or livelihoods in Pasakha.

Health officials admit that no research has ever been carried out to determine the impact of pollution on people’s health or livelihoods in Pasakha.

“The one glaring gap is the lack of information for us as a service provider, health provider, particularly, to provide the most effective responses. We do not have, at this point, adequate information. Especially when it comes to environmental health issues,” said Dr Dorji Tshering, the Chief Medical Officer with Phuentshogling Hospital.

The absence of such evidence means communities continue to live without regular health monitoring or targeted interventions.

Residents say the last time they underwent a medical check-up was during the Nationwide Non-Communicable Disease Screening held last year.

“There are no clear policies for us to follow or use as guidance to support the communities. Right now, it’s quite confusing because when policies are unclear, it becomes difficult to take proper action,” said Uttar Kumar Rai, Phuentshogling Thrompon.

For now, the Department of Industry monitors factories daily.

According to the department, ten companies have been penalised for excessive emissions, illegal waste dumping, and not complying with environmental standards. But without proper data, the long-term effects on health and livelihoods remain unaddressed.

For residents of Samphelling Gewog, life continues under a cloud of uncertainty. Until research is carried out and policies enforced, communities will have to live with pollution, waiting for concrete action.

Tshering Zam & Sangay Chezom