The DAMTSI programme, aimed at instilling integrity and moral values in young children, is facing implementation challenges, especially in private Early Childhood Care and Development centres. As part of the Youth Integrity Programme, the initiative hopes to promote accountability and reduce corruption from an early age. But a recent report reveals the gaps in training and resources that may be hampering its success.

The DAMTSI programme, aimed at instilling integrity and moral values in young children, is facing implementation challenges, especially in private Early Childhood Care and Development centres. As part of the Youth Integrity Programme, the initiative hopes to promote accountability and reduce corruption from an early age. But a recent report reveals the gaps in training and resources that may be hampering its success.

An Integrity Education Handbook for ECCD facilitators titled the “DAMTSI Activity Book was launched in 2021.

An Integrity Education Handbook for ECCD facilitators titled the “DAMTSI Activity Book was launched in 2021.

The DAMTSI programme, short for Developing Accountable and Moral, Trustworthy, and Successful Individuals, is designed to teach children aged two to five values like integrity and honesty.

It also involved parents in the learning process.

Developed by the Anti-Corruption Commission in collaboration with the Education Ministry, the book serves as a key resource for facilitators.

However, ACC’s evaluation report this year shows that private ECCD centres are facing more challenges than public ones in implementing the programme.

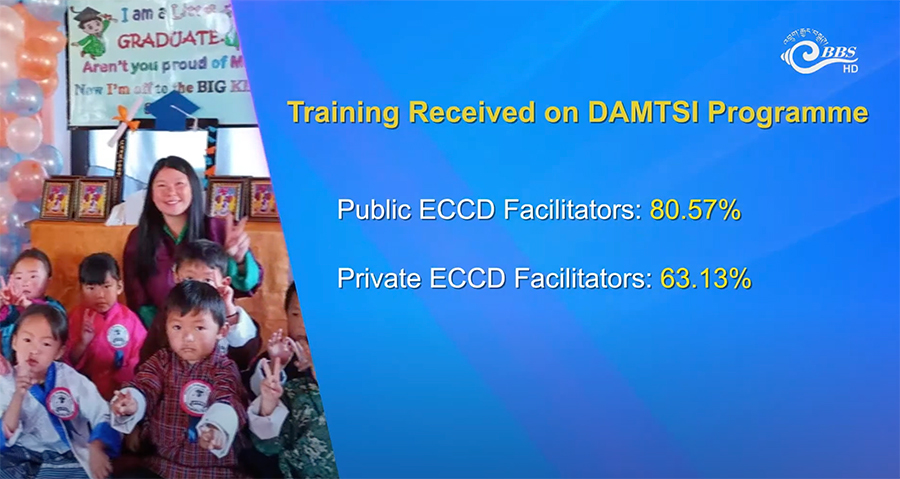

One major concern is the lower training coverage, just over 63 per cent of private centres received training compared to more than 80 per cent of public centres.

One major concern is the lower training coverage, just over 63 per cent of private centres received training compared to more than 80 per cent of public centres.

“The lack of materials and budget can greatly impact how we deliver the DAMTSI programme in our centre. Firstly, we need a lot of training for our educators as DAMTSI is a very new concept, and also, resources and materials are very important,” said Lhazom Tshering, Director, Play and Learn ECCD Centre.

Parents, too, are facing difficulties applying DAMTSI values at home. Common challenges include lack of time, digital distractions, and children’s shifting moods.

“The challenges I see in applying and implementing this programme and making it more experiential at home are due to the presence of digital devices. It’s a digital age, and we find it challenging to deal with content on the devices they are used to. So in that case, we find it challenging to manage the time, and how could we cater to something beyond those devices?” questioned Ugyen Lhendup, a parent.

Facilitators report that concepts like “corruption” are particularly hard for young children to grasp, and limited training leaves many educators unprepared.

“I think if we receive more training on the DAMTSI program, we can teach the students more effectively. To understand the programme, it is important that we first study and learn it ourselves. So, we would be grateful if more training opportunities were provided in the future,” said Phub Zam, a facilitator at Play and Learn ECCD Centre.

“Although the programme is very helpful, it is difficult for the children to understand. For example, topics like corruption are challenging to explain, unlike concepts such as integrity and honesty,” said Jigme Zangmo, Facilitator, Silidraphu ECCD Centre.

The report also notes that many centres lack adequate learning materials, activity guides, and even basic infrastructure. Budget constraints are preventing replacements or upgrades.

The Ministry attributes the gap in training to lower participation from private facilitators. Those who do attend are said to receive thorough instruction and implementation guidance. Resource allocation, meanwhile, depends on need and availability at both central and district levels.

To address these challenges, the report recommends better resource allocation, more comprehensive training, stronger parental engagement, and improved monitoring mechanisms.

With the right support, stakeholders hope that the DAMTSI programme can still meet its goal of shaping morally grounded individuals from a young age.

Jamyang Loday

Edited by Tandin Phuntsho